This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

True crime has always been a popular genre, from the murder ballads of centuries past to the documentaries, podcasts and books that we consume today. True crime stories trend, dominating news cycles and our conversations with friends and colleagues, with everyone offering opinions or even, in these days of web sleuths, getting involved as have-a-go amateur detectives. There’s clearly something about true crime stories that draws us in and captures our imaginations — but is our love of true crime a useful tool for justice, harmless fun, or ultimately damaging?

Many people over the years have considered the ethics of true crime. Questions over exploitation are some of the most frequent points made — true crime has been described as ghoulish, relishing in descriptions of murders while ignoring the fact that the victims were real people, some with surviving loved ones who are retraumatised by a cultural fascination with the violent end that the victims faced. Others see true crime as a way to highlight how marginalised people are ignored, particularly by the systems that are supposed to protect them, and insist on justice and reform. Some true crime narratives have undoubtedly led to the glorification of some killers — Ted Bundy, Richard Ramirez and Chris Watts are some of the murderers who have their own grotesque fanbases, many of whom focus on their looks.

However, society’s focus on true crime has also forced change. Nikki Addimando, a criminalised survivor of severe domestic abuse, was released early in 2024, in large part because of attention brought by a podcast about her case. In the UK, the attention on the murder of Sarah Everard by active police officer Wayne Couzens, and the resulting attacks on feminist protestors by police, led to increased scrutiny on the police force and the bringing to light of multiple other crimes and abuses by serving officers.

The ethics of true crime can be as complex as the crimes that this genre deals with; while there are many reasons why people might read true crime, there are also some legitimate reasons to be cautious and to critique the hold that true crime has over society.

Finding the Facts

Many true crime writers go to great lengths to ensure that their research and writing are conducted in as ethical a way as possible. A number of true crime writers come from an investigative journalism background, and receive specific training on how to handle sources, approach interviewees, and protect the anonymity of sources. Many writers also bring their own ethical stances into their approach to different cases; for example, Carol Ann Lee chose not to meet convicted murderer Jeremy Bamber in person when she was writing The Murders at White House Farm, as she did not want her objectivity to be affected by building a personal connection with him, particularly as Bamber still maintains his innocence. While some readers may disagree with this particular stance — and indeed, many true crime authors have built personal connections with killers while still maintaining balance and fairness in their writing — it is clear that Lee is nevertheless making a choice based on her own carefully considered ethics, and the resulting book does take a balanced look at both the facts of the case and Bamber’s own claims, reaching the conclusion that the most likely explanation for events at White House Farm is the one reached by the courts.

Some true crime writers cannot help having a personal connection to the killers that they write about. Ann Rule’s most famous book, The Stranger Beside Me, is an account of the murders committed by Ted Bundy, but also includes Rule’s unique perspective as someone who was friendly with Bundy before he was revealed as a killer, and who genuinely enjoyed his company. In The Stranger Beside Me, Rule takes a frank look at her own relationship with Bundy, without downplaying the horrific crimes that he committed. Similarly, FBI behavioural scientist John Douglas writes in Mindhunter about his personal involvement in the investigation of many serial killer cases, including the connection he has built with murderer Ed Kemper. At one point, Douglas admits that he does like Kemper as an individual, but that this does not matter in the light of the violent crimes that Kemper committed, or the impact on his victims’ loved ones.

Some true crime writers have a personal connection not to the killer but to others involved in the case. Kim Reid, author of No Place Safe: A Family Memoir tells the story of the impact of the 1979-1981 killings committed by the Atlanta Monster. Reid’s mother was the first Black woman detective to work on this case, and Reid’s story details the impact of the murders—whose victims were Black and often overlooked by the almost entirely white police force,—on both her local Black community and the privileged, mostly-white school that she attended. Although the subject matter is true crime, Reid’s book is specifically a memoir, making it clear that she is writing from her personal perspective and using her childhood memories, while still bringing in the facts of the case and the social context that surrounded it.

Victims and Survivors

The treatment of victims, and by proxy their surviving loved ones, by true crime media, is one of the areas where arguments about ethics are most frequently made. The now adult children of the women murdered by Peter Sutcliffe, dubbed The Yorkshire Ripper, criticised a Netflix documentary because of its ‘glorification’ of the killer, including centering him in the show’s title. The families of Sutcliffe’s victims have had to deal with their murdered loved ones being sidelined or denigrated by the media since the murders were committed — Sutcliffe primarily targeted sex workers, and the stigma against this marginalised group led to the police, society and contemporary news sources dismissing them as unimportant. Indeed, when Sutcliffe murdered a young woman who was not involved in sex work, papers infamously claimed that ‘the Ripper has killed his first innocent victim’. A lack of focus on the rights and feelings of victims’ families was also apparent when Netflix released another show about a notorious serial killer, Jeffrey Dahmer. Dahmer’s victims’ families were not consulted about the show, and did not know about it until it was released; while Netflix was not required to approach them, as it drew on details of the case that were already in the public domain, the lack of courtesy and attention to the survivors’ feelings was crushing for the families.

The sidelining of these surviving family members speaks to another true crime trend that has frequently been criticised: the treatment of different marginalised groups. Sutcliffe’s victims were working-class women, many of whom did sex work; Dahmer’s victims were predominately young gay men of colour, and a number of them were also sex workers. Societal prejudice against people from these marginalised groups has often led to true crime media depicting these victims, and others like them, as somehow deserving of the violence committed against them: people who lived ‘high-risk lifestyles’, and who should have expected to be targeted as a result. By contrast, it has frequently been noted that true crime publications centre and empathise with middle-class, traditionally attractive, white cishet women who become the victims of murders, abductions or other crimes, a bias often referred to as ‘missing white woman syndrome’. Photogenic, privileged white women or children receive a disproportionate amount of attention and empathy when their lives (and deaths) become the subject of true crime media — BIPOC women, LGBTQ+ people and other marginalised individuals are not given the same kind of care or focus. This institutionalised racism and prejudice that is found in many police forces worldwide has been explored by some true crime authors, including Tanya Talaga, an Anishinaabe author whose book Seven Fallen Feathers explores the history of anti-indigenous racism in Canada through the cases of the murders of seven Indigenous high school students in Ontario.

How can we combat this disparity in true crime? Centreing the feelings of survivors or victims’ loved ones is one way, and many have written true crime books of their own. Remembered Forever, by Luke and Ryan Hart, is the account of their lives and the events leading up to the murders of their mother and sister, Claire and Charlotte, by their abusive father. Not only does their book give an important insight into how coercive control can work—true crime here being a force for good, potentially giving people going through coercive control context that can help them recognise this form of abuse—but it also brings the victims to the fore and celebrates them as the real and complex people they were. The Hart brothers deliberately chose to omit their father’s name from the entire narrative, in contrast to contemporary news reports that centred him, referred to his victims by their relationships to him, and depicted him as ‘a good man who’d just snapped’.

Similarly, Love As Always, Mum xxx centres victims of serial killers Fred and Rose West who are often overlooked: the Wests’ own children. Mae West, the author, describes her childhood growing up in the ‘House of Horrors’, at constant risk of violence or sexual abuse, and aware of the violence going on elsewhere in the house, including the victims buried in the cellar and garden. Mae West’s account shows her own struggle to reconcile the Wests’ crimes with the parents she knew, who were abusive in multiple ways, but also showed moments of love and kindness that were significant to Mae and her siblings as they grew up. Books like Love as Always, Mum xxx challenge the sensationalism that true crime can sometimes dabble in, showing that serial killers are not fantastical monsters, but mundane humans with families, who still choose to do terrible things.

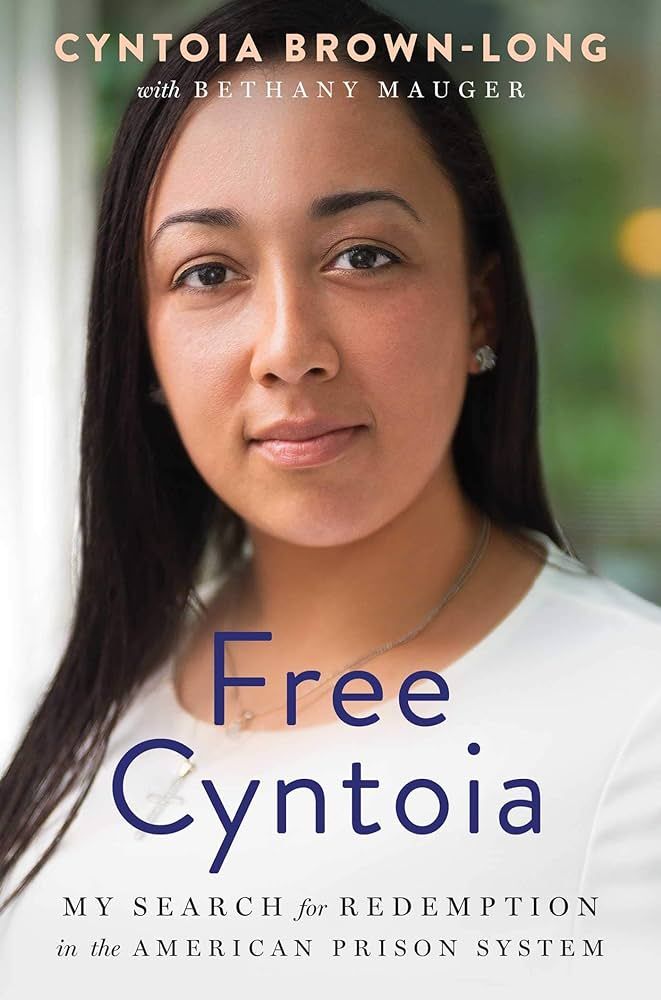

Criminalised survivors — people who are punished with incarceration for fighting back against their abusers — have also used true crime and memoir as a way of telling their side of the story. Free Cyntoia, written by Cyntoia Brown-Long and Bethany Mauger, is one such narrative. Brown-Long was convicted of murder when, after many years of child sexual exploitation, trafficking and other forms of abuse, she killed one of the men who had harmed her. Brown-Long’s story not only tells her side of the action that led to her imprisonment, but looks at the realities of the American prison system and its impact on incarcerated people.

True crime is a complex area: messy and nuanced, with the potential to sensationalise and exploit, but also the possibility of making real and important contributions to our understanding of the most dangerous parts of humanity, and the impact of violence and harm on victims and survivors. Ethical true crime stories are certainly achievable, but writers need to take care to avoid glorifying violence or handwaving systemic prejudice, to focus on balance and facts, and to centre and respect the people who have been harmed.

If you want to learn more about why we are so fascinated by true crime, read Why Do People Read True Crime? To find out more about the people true crime often overlooks, try Books About Missing and Murdered People of Color That Deserve More Attention.