Jimmy Carter, president of the United States from 1977 to 1981 and a statesman for four decades after that, has died in his birthplace, Plains, Georgia. In early 2023 he chose to forgo further treatment for cancer and entered hospice care, where his wife Rosalynn joined him shortly before her own death in November 2023.

If Jimmy Carter, from the peanut fields of Georgia, was not “America’s greatest ex-president”, as many called him, he was its most visible for a long time. The plain-spoken earnest Baptist who still taught Sunday school and counted Bob Dylan among his friends was ahead of his time in advocating for human rights around the world. A nuclear engineer, he warned of threats to the environment. He put more women in government than his predecessors and he worked for peace in the Middle East, succeeding in the Camp David Accords with Israel and Egypt and falling short with Israel and Palestine.

President Jimmy Carter (centre) at the White House with President Anwar Sadat of Egypt (left) and the Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, for the signing of the Israel-Egypt peace treaty 26 March 1979. The treaty signing followed the three men’s negotiation of the Camp David Accords the previous September Jimmy Carter Library

While not central to his politics, Carter’s cultural impact after the Watergate scandal was broadly positive, and transformative in some cases. In 1978, he opened the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art, a bold imposing block of glass and steel, designed by IM Pei, at the base of the US Capitol which affirmed modern architecture in a staid city. At the gallery’s opening, Carter declared that “we have no ministry of culture in this country, and I hope we never will. We have no official art in this country, and I pray that we never will. No matter how democratic a government may be, no matter how responsive to the wishes of its people, it can never be government’s role to define exactly what is good, or true or beautiful. Instead, government should limit itself to nourishing the ground in which art and the love of art can grow.”

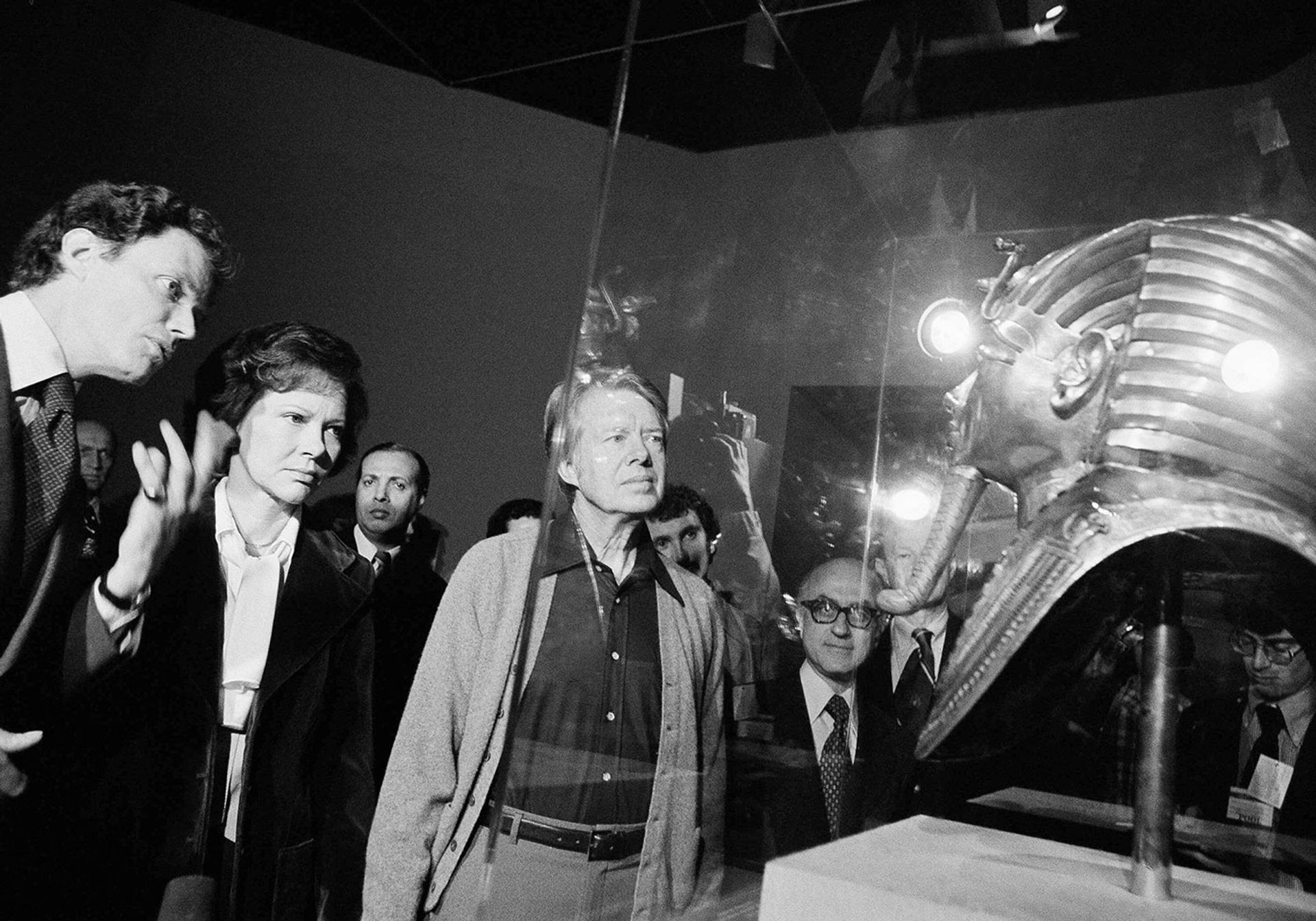

President Jimmy Carter, centre, and his wife Rosalynn Carter, second left, are shown the golden mask of Tutankhamun by J. Carter Brown (left), director of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, during the Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition at the museum, 12 March 1977 Peter Bregg / Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo

Jimmy Carter’s openness to art and music

Carter’s openness to a wide range of art and music would be his lasting cultural legacy. “I’ve called him as close to a Renaissance man as we’ve had in the White House in modern times,” said Stuart E. Eizenstat, Carter’s Chief Domestic Policy Adviser from 1977 to 1981. Under Carter, Congress doubled the budget of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), the closest agency in the US to a cultural ministry. After Carter left office, NEA-funded art that the Christian Right and its allies found obscene fuelled a culture war that still rages. In 1979, the Rev Jerry Falwell founded the Moral Majority to leverage resentment among southern Christian Evangelicals who gave the “born-again” Georgian a narrow victory in 1976. The Christian vote sent Carter back to Georgia after one term.

In 1980, Carter signed a bill assigning a site for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, later designed by Maya Lin, an austere slab of black marble inscribed with the names of Americans who died in a brutal, divisive, war. Carter was gone when Lin’s design was commissioned (another defining modern structure in Washington, DC), but the project that he helped launch weathered bitter criticism. It is now a rare place that, echoing Carter’s openness, draws visitors of all political backgrounds. In that spirit, Carter issued an amnesty for US draft evaders and exiles on his first day in office.

Andy Warhol poses next to his screenprint Jimmy Carter 76, at a reception on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, 14 June 1977. The work was part of a collection titled Inaugural Impressions on display in the offices of the House Administration Committee Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo

How Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign exploited his image

The little-known Jimmy Carter emerged as a presidential candidate in 1975. It was easier then to see what art did for him than what he did for art. In a US landscape saturated with commercial logos and faces, Carter’s campaign exploited his image like a Warhol Brillo box. He was photographed from point-blank range, with an unusually wide toothy smile, and piercing blue eyes. His brand had a ringing religious fervour. While not an art collector, Carter befriended musicians like Willie Nelson, Greg Allman, Marshall Tucker and Stephen Stills, and claimed to be a distant cousin of Elvis Presley, who would become a fan. Another friend was Bob Dylan, whom Carter counselled when Dylan considered converting to Christianity.

Carter won counter-cultural credibility when the “Gonzo” journalist Hunter S. Thompson (“Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail,” 1976), raved after hearing the Georgia Baptist deplore the role lawyers play in US society. Carter somehow survived Thompson’s praise and a 1976 interview with Playboy where the pious man admitted “lusting after women” in his heart.

President Jimmy Carter explains the use of solar panels to provide hot water for the White House, 20 June 1979. Carter endorsed the use of solar power as part of a national plan to conserve energy and develop alternative energy sources Jimmy Carter Library

Artists were drawn to Carter and made posters for the 1976 campaign. Andy Warhol travelled to Carter’s home in tiny Plains, Georgia, and made three portraits. Jimmy Carter I, was a photo-collage of the candidate in a pensive mood, in primary colours anticipating Shepherd Fairey’s “Hope” portrait of Barack Obama. The Carter campaign sold prints in a series of 50 for $1000 each. Warhol constructed two other portraits around Carter’s signature smile, and lingered long enough in Plains to paint Carter’s mother, Lillian, and other relatives. “They were very normal. We got along very well …. Jimmy Carter gave me two big bags of peanuts which he signed. That made the whole trip worthwhile,” Warhol said. (In 1980, Warhol abandoned Carter and made a portrait of Ted Kennedy, who challenged Carter for the Democratic Party nomination for president.)

Warhol and Rauschenberg created Jimmy Carter’s “Inaugural Impressions”

For Carter’s inauguration in 1977, the portfolio “Inaugural Impressions” featured work by the artists who supported his campaign: Warhol, Jacob Lawrence, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, and Jamie Wyeth. Warhol, who had a better offer in Tehran, skipped the ceremony.

Yet the man with an ear for music often had a tin ear for politics, or an aversion to operating tactically. Sanctimony and a micromanaging engineer’s exactitude did not help. By the end of his term, the obstacles overwhelmed Carter—soaring inflation and interest rates, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the long confinement of US hostages at the American embassy in Tehran.

The 11th-century Crown of St Stephen on show in the Hungarian Parliament Building, Budapest. President Jimmy Carter ordered its restitution to Hungary in 1978. It had been kept at Fort Knox after being given by a Hungarian army officer to US forces in 1945 before Soviet army members could seize it Peter Barritt / Alamy Stock Photo

Jimmy Carter restituted Crown of St Stephen to Hungary

Carter’s critics had already attacked him in 1978 for ordering the return to Hungary of the jewelled 11th-century Crown of St Stephen, which the Hungarian army gave to US forces in 1945 before Soviet troops could seize it. When Hungarian émigré nationalists and Cold Warriors protested at the idea of returning it to a Communist country, Carter said he sent the crown back from Fort Knox to reward Hungary’s progress on human rights. The crown’s return, an early example of US restitution of cultural property, raises questions about objects that Carter might have returned in a second term. “He understood the cultural and artistic significance of what had been captured during the war,” said Eizenstat, who would later lead US efforts in Holocaust Era restitution. “I think he would have continued to do that for anything we had in our possession that had been taken.”

Barely remembered today is Carter’s Comprehensive Employment Training Act, a broad, federally funded, initiative and the largest jobs programme for artists since the Works Progress Administration (WPA) of the 1930s. From 1974 to 1981, artists in a range of media were paid to work four days a week in local organisations and one day a week in their studios. Originally a Republican patronage strategy, CETA ended up supporting thousands of artists around the US during the Carter years. The sculptor Ursula von Rydingsvard, the film-maker Spike Lee, the photographers Dawoud Bey and Larry Racioppo, and the artist Judy Baca (The Great Wall of Los Angeles) held jobs supported by CETA. Opponents ridiculed what they called a “make-work” program and CETA withered under the Reagan administration after 1981.

Jimmy Carter greets a young Nepali boy during the Carter Center’s observation of Nepal’s constituent assembly elections in November 2013 The Carter Center

Carter’s moral rhetoric made him an easy leader to attack. “Carter’s style of leadership was and is more religious than political in nature. He was and is a moral leader more than a political leader,” his former speechwriter Hendrik Hertzberg recalled in a 1999 lecture on his character. Before Anwar Sadat was assassinated in 1981 for making peace with Israel at Camp David, he wrote a note saying, “Jimmy Carter is my very best friend on earth … Brilliant and deeply religious, he has all the marvellous attributes that made him inept in dealing with the scoundrels who run the world.”

As an ex-president, not needing voters or allies, Carter travelled the world building housing, monitoring elections, fighting tropical diseases, and meeting with pariah dictators when few leaders would. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002.

Jimmy Carter and Rosalynn Smith on their wedding day, 7 July 1946. Jimmy Carter took up painting while serving in the US Navy 1946-53 Jimmy Carter Library

At home in Plains, Georgia, Carter wrote more than 30 books, made wooden furniture and returned to oil painting, which he had taken up while serving in the US Navy 1946-53. A festive scene of himself with Menachem Begin and Sadat celebrating Camp David looks like paper dolls painted by an excited child, but portraits of his mother and of a shy young Rosalynn show a tender sensitivity. His pictures have not made it to Sotheby’s, but one broke one million dollars at an auction to benefit the Carter Center in Atlanta.

As Carter the politician learned, it helps to know your audience.

James Earl Carter, born Plains, Georgia, 1 October 1924; served US Navy 1946-53; Georgia State Senator 1963-67; Governor of Georgia 1971-75; President of the United States 1977-81; Fulbright Prize 1994; Presidential Medal of Freedom 1999; Nobel Peace Prize 2002; married 1946 Rosalynn Smith (died 2023; one daughter, three sons); died Plains, Georgia 29 December 2024