Josh Brolin’s From Under The Truck is not exactly a celebrity autobiography, or a now-sober guy’s literary remembrance of wild times past, or a son’s memoir about loving and losing a difficult parent, although at points, depending on where you open the book, it resembles all of those things. It’s a mosaic of bright shards—dated short pieces written in the emotionally raw, low-exposition manner of journal entries, arranged nonlinearly but associatively, as if we’re looking at the story from the perspective of a Josh Brolin who has come unstuck in time. At one point Brolin toggles between memories from the sets of two movies: The Goonies, which launched his acting career in 1985, and the Coen Brothers’ No Country For Old Men, the project that lifted Brolin out of the professional doldrums in 2007. At another point, a story from the mid-1970s about the “utter fucking havoc” and unimaginable stress of the Rancho Palos Verdes home Brolin and his younger brother shared with their mother (and the wolves, mountain lions and coyotes she kept as pets) is followed immediately by a recollection, from 2022, of teaching his own child to swim, with tender care.

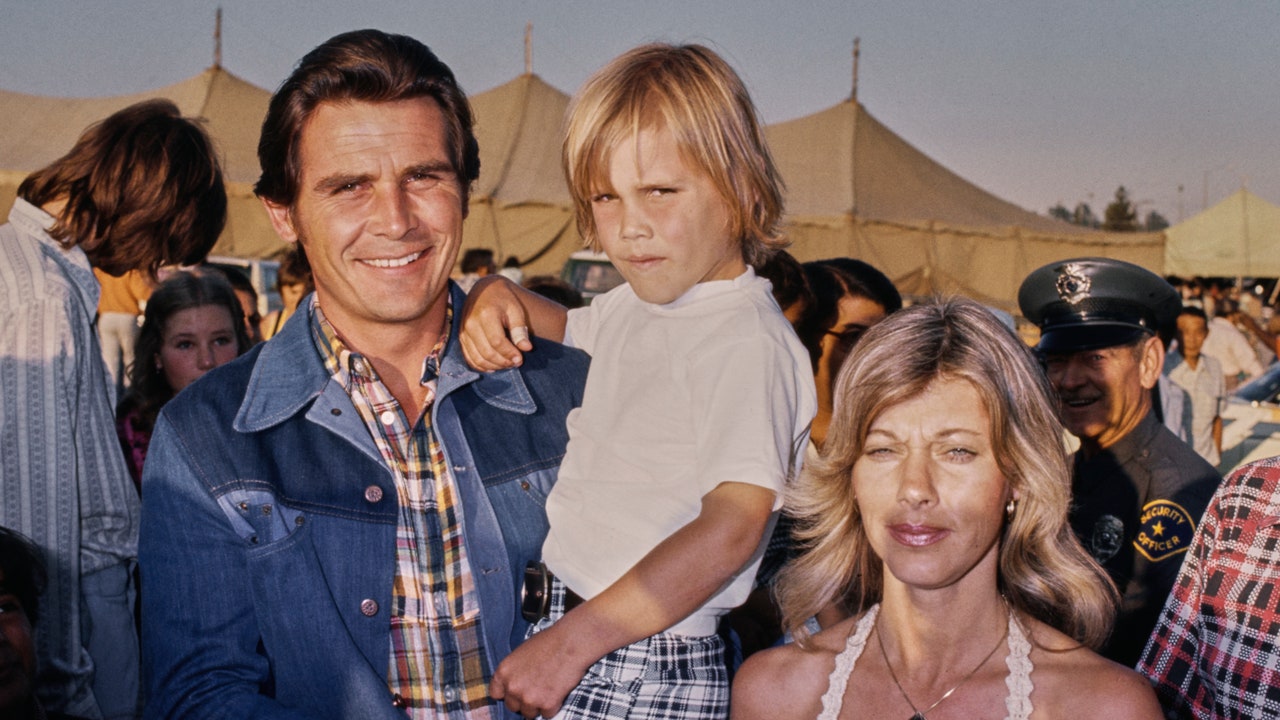

But even those examples make the book sound more straightforward than it is. The straightforward version of this book might have framed Brolin’s late-40s ascent to the franchise-picture A-list as a happy ending—evidence of childhood trauma overcome, the reward for hard-won sobriety. Brolin’s version of the story, in 228 pages, contains only one passing reference to Dune; the word “Avengers” does not appear, nor does the name “Thanos,” and “marvel” is used solely as a verb. Instead, over the course of those 228 pages, a narrative arc comes at us sideways and in pieces. On page six, Brolin tells us “I was born to drink. I was birthed to drink. My mother drank exactly like I did, and I was raised to be a man and drink like the male equivalent of my mother.” She was Jane Agee, who raised Brolin and his brother at the ranch while Brolin’s father, the actor James Brolin, worked on shows like Marcus Welby, M.D.; she died in 1995, the day after Brolin’s 27th birthday, of injuries sustained in a car accident that Brolin writes about as a flat inevitability, part of the logical trajectory of her life: “A typical Jane speed of around seventy in a thirty-five wasn’t rare. She hit that tree and that tree wasn’t going anywhere.” Before that, Agee gives her sons a childhood that reads more like ritual indoctrination into a cult of toughness; at one point he recalls his brother cowering behind a door while Agee screams, “YOU GET OUT HERE RIGHT NOW AND SPEND TIME WITH THE WOLF!”

Brolin carries that programming with him from his young adulthood—in which he feels out of place on movie sets and far more at home running with a Santa Barbara surf-punk gang called the Cito Rats—until long after her death. It comes to a head in 2008, when Brolin—overserved to the point that no less a S-tier imbiber than Sean Penn has already advised him to cool it—lets the Cabernet talk while accepting a Best Supporting Actor prize from the New York Film Critics’ Circle for Milk. “I was going to be my mother’s son: a cowboy, a drunk, a rabble-rouser—my own man,” he thinks to himself beforehand; as he delivers a name-naming, fuck-the-doubters-and-haters rant in front of a room full of his aghast peers, images of himself cleaning up wolf shit flash in his brain. When it’s over the devastation is total; his publicist can’t look him in the eye.

This moment does not mark the end of Brolin’s career, or his partying days—by this point we’ve already read about him, years later, reporting to the set of Inherent Vice not long after being gut-stabbed while drunk on the street in Costa Rica with his future wife Kathryn and worrying he’ll rip his stitches while roughing up Joaquin Phoenix on camera. That happened in 2013, a year that began with Brolin being arrested for public intoxication in the early hours of New Year’s Day. In 2023, on Instagram, Brolin posted a picture of a 10-year AA chip made out to “Josh Fu€kin Brolin”; the book leaves us to do the math and to infer how precisely he made it across the river. Tidiness and finitude aren’t the point of a story told in this fashion, anyway. The point of the story is that even as he’s on set worrying about his stitches he and Kathryn are talking about taking another trip—to Costa Rica, of course. As Brolin explains it, in a sentence that jumps its immediate context, seemingly speaking instead to the project as a whole: “It haunted me, what happened, and whatever haunted me I had to confront again and again until it either killed me or ceased to have that power.”