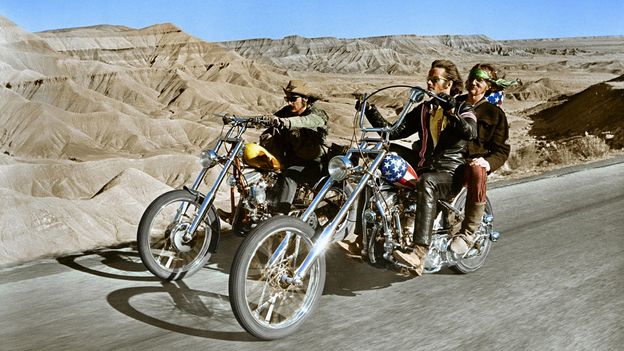

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe cult classic’s guerilla techniques and daring subject matter helped to kickstart a new era. Just before its release in 1969, the BBC interviewed its director, Dennis Hopper, discovering an actor as idiosyncratic as his film.

On 17 October 1969, Easy Rider burst on to cinema screens through a psychedelic haze. Infused with rock music, free love and drug-taking, this low-budget, freewheeling road movie vividly captured the counterculture spirit of the late 1960s, as well as the US’s bubbling social tensions.

The film tells the story of two free-spirited bikers, moustachioed hippy Billy, played by its director, Dennis Hopper, and leather-clad Wyatt, played by its producer, Peter Fonda. Easy Rider starts with Billy and Wyatt smuggling cocaine out of Mexico to sell to a Los Angeles drug dealer, played by famed music producer Phil Spector (whose performance seems even more sinister in the light of his 2009 murder conviction). The pair, now flush with cash, then resolve to ride across the US to New Orleans in time for Mardi Gras.

As they embark on their odyssey through the sweeping American landscape to the strains of Steppenwolf’s Born to Be Wild, they encounter characters who embody some of the conflicting world views prevalent in the US at the time, from an alcoholic civil-rights lawyer (played by Jack Nicholson) to a corrupt sheriff, from a hippy commune to small-town bigots. The film-makers paint a portrait of a country in flux. The slogan on the posters was: “A man went looking for America. And couldn’t find it anywhere…”

A month before Easy Rider’s release in 1969, Hopper sat down with the BBC’s Philip Jenkinson for the programme Line Up. Decked out in clothes similar to those of his character Billy, Hopper’s interview was intriguing, erratic and, at times, as confusing as the cult movie he had just made.

He explained to the BBC that he had wanted “to basically make a movie about what was happening in America at that moment”. The 1960s were a tumultuous period for the US, as the country went through rapid and momentous cultural shifts. The decade had already witnessed the civil rights movement’s push for equality, growing anti-war protests as the Vietnam war escalated, and a series of shocking assassinations of political figures such as John F Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.

The gap between generations seemed to be widening. Many baby boomers had embraced the new music and culture, experimenting with drugs and sex, and often outright rejecting the more traditional values and materialism of their parents. Hopper felt that there was nothing in the cinema that spoke directly to these young people. There was nothing that showed their hopes and fears, how they desired to live and how those aspirations had opened up deep divisions in American society. He told the BBC in 1969 that he hadn’t seen any movies “that made a social commentary about what was going on”.

“Yes, [the studios] make them about the [American] Civil War, they make them about slavery, or they make them about the Korean War, but, I mean, something that was really going on at that moment. Very few people go out and make a movie about that, especially in Hollywood.”

A megalomaniac

Easy Rider was not just unorthodox in its choice of subject matter, but also in its wildly chaotic film-making. With a limited budget of just $400,000 (£305,620) from Columbia Pictures – which at times meant that Fonda had to pay the crew out of his own pocket – the production adopted a DIY approach. Crucial to the film’s narrative was the idea of the road as a symbol of freedom and possibility, so Hopper needed to capture shots of Billy and Wyatt as they cruised down the seemingly endless highway. This kind of filming would usually have been done by hiring a camera truck with a radio. Instead, the film-makers bought a 1968 Chevy Impala convertible, with the aim of selling the car at the end of the film to recoup some money. Cinematographer László Kovács then stuck a camera on the back of it with plywood and sandbags, and sat in the back seat filming Fonda and Hopper as they rode their Harley-Davidson motorbikes on the open road, making hand signals to communicate what they should do. The production also saved money by filming in real locations, rather than building expensive studio sets, and by shooting scenes in natural light using handheld cameras, which added to Easy Rider’s feeling of unfiltered authenticity.

But the film’s production was far from plain sailing, not least because Hopper was a volatile character. He confessed to the BBC in 1969 that he had been blacklisted in Hollywood because of his tendency to fall out with directors. “I took direction when I respected the man,” he said. “If I didn’t respect the man, and most of the time I didn’t, I didn’t take direction.” Now, for the first time, he was the director himself, and he ended up battling for control of every aspect of the film-making process. At one point, he had a physical fight with a camera operator who wouldn’t hand over the footage he had shot.

That would not be the only “heated disagreement” the director would have on set. Actor Rip Torn was initially hired to play Nicholson’s role, but he left a few weeks into the shoot after a fight with Hopper. The actor would successfully sue Hopper in 1994 for defamation when the director claimed that Torn had pulled a knife on him during the fight – saying, in fact, that the reverse was true. In Jenkinson’s interview, the director did concede he was “difficult to work with”. Fonda put it more frankly when he spoke to the BBC’s Will Gompertz in 2014: “Hopper was a bit of a megalomaniac.”

But Hopper took his craft seriously and was committed to his vision. He told the BBC that he “had been trained in method acting” and “not to have preconceived ideas” about how a scene should play out. When he had worked with James Dean as a young actor on Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Giant (1956), Dean had told him, “Don’t act smoking a cigarette, just smoke it.” Hopper took this advice to heart. To give realism and a loose spontaneity to this tale of the counterculture, he – along with Fonda and Nicholson – took liberal amounts of drugs and alcohol during the shooting of the movie. Scenes were directed in documentary style, with the – often stoned or high – actors improvising scenes and dialogue.

Nicholson told Time Magazine in 1970 that he “smoked about 155 joints” during the multiple takes of a scene in which the two bikers introduce his character, George, to marijuana. The real acting challenge for him proved to be remembering, after all those joints, to play George as if he was clear-headed at the start of the scene. “Keeping it all in mind stoned, and playing the scene straight, and then becoming stoned – it was fantastic,” he said.

The film-makers took full advantage of the abandoning of the Hays Code in 1968. Hollywood’s self-imposed guidelines had prohibited, among other things, profanity, nudity, realistic violence and drug use. When the Code was replaced by the MPAA rating system, Easy Rider made the most of this new freedom, and its frank portrayal of drug-taking without judgement helped it to become a cause célèbre upon its release. Hopper defended the drug-taking to the BBC, saying that “it would be unrealistic of these two boys in America not to smoke pot”, and he claimed that their cocaine smuggling was no more immoral than other capitalist ways of making money. “Perhaps all of us are involved in criminal acts of one kind or another,” he said.

And Easy Rider doesn’t seek to present the bikers as heroes or even necessarily as good people, just as a reflection of America. “Well, I think they are as good as their leaders, don’t you? I think people are as good as their leaders,” said Hopper. The film, at times, portrays a deeply unsettling image of the US its protagonists live in. It makes clear the open hostility and brutal violence that individuals who are seen as outsiders can face.

A new era

But the way Billy and Wyatt dressed, their disillusionment with establishment values and their search for identity and purpose struck a chord with many young Americans.

So did Easy Rider’s rock ‘n’ roll jukebox soundtrack, which managed to capture the restless spirit of the times. Songs by Jimi Hendrix, The Byrds, The Band and others were originally just music the film-makers liked. They were only meant to act as placeholders while Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young worked on a proper score. But Easy Rider ended up being edited to the songs, meaning that a huge portion of the film’s final budget then had to be spent on licensing to clear them for use.

Despite initially being released in only one New York cinema, Easy Rider resonated with American youth, quickly becoming a critical and commercial hit. Hopper won the First Film Award at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival, and Nicholson and Easy Rider’s screenplay both received Oscar nominations. The movie would go on to gross more than $60 million (£45.8m) worldwide.

Hollywood was blindsided by the sudden popularity of a film made on a shoestring budget outside the studio system. Easy Rider’s box-office success helped kickstart an era where studios gave young directors, such as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg, much more creative control and freedom to experiment. These directors would then go on to define US cinema in the 1970s.

Hopper himself seemed bemused by this newfound acceptance by a Hollywood that had previously rejected him. “It’s like you are on an elastic band. You run so far away that they snap you right back into the middle, and suddenly you’re in the middle surrounded by the establishment,” he said.

But he remained cynical about his status. “They are patting you on the back and loving you and pulling you to their bosom. Until you are no longer useful to them, and then they toss you away again.”

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.