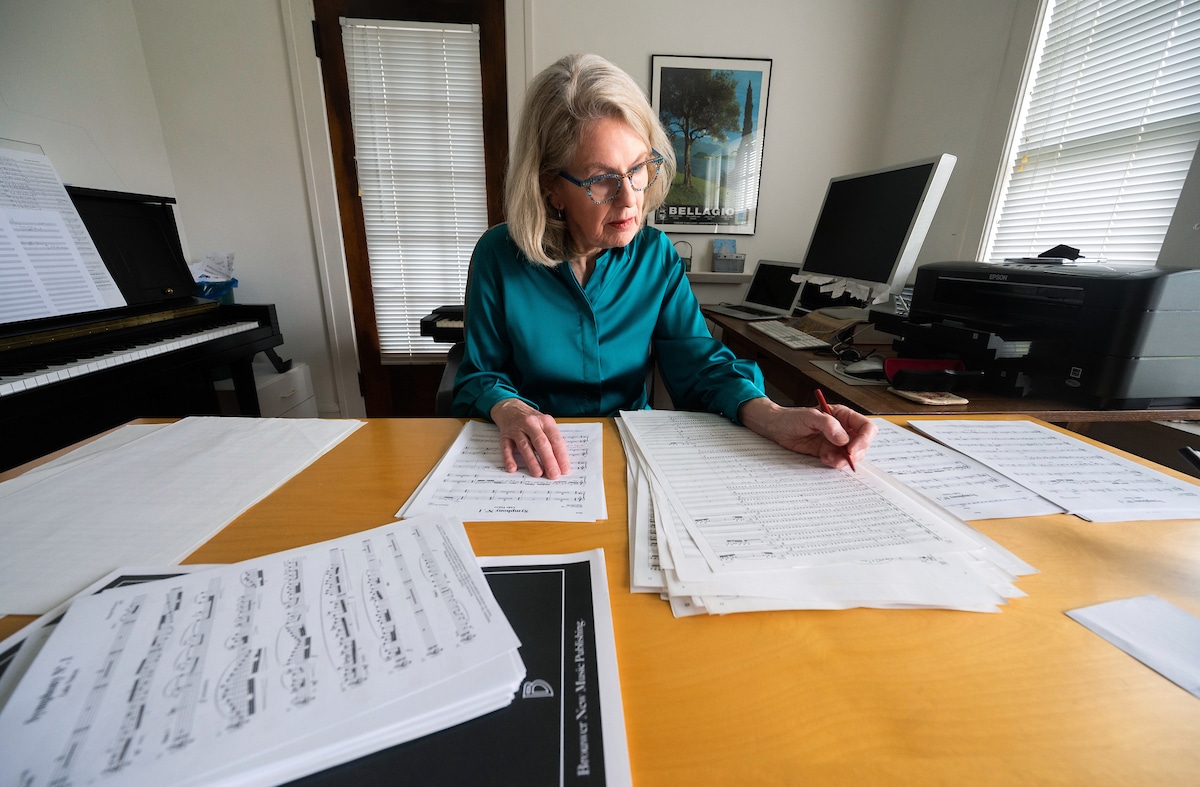

One line you’ll probably never see on Margaret Brouwer’s lengthy “about” page is any reference to retirement.

Never mind that Brouwer will soon turn 85. Cleveland’s unofficial composer laureate has no intention of stopping, retiring or even of slowing down. On the contrary, she’s got more plans than ever.

“All fall, I’ve just had one thing after another,” said Brouwer, by phone from Cleveland, where she’s spent much of her long career. “I’ve been really busy.”

Much of what’s been keeping Brouwer so engaged has taken place close to home. Although, at this point, Brouwer’s music is liable to pop up just about anywhere, many of her most active and devoted interpreters are right here in Northeast Ohio, where she’s lived since 1996, when she began a 12-year stint as head of composition at the Cleveland Institute of Music (CIM).

The list of Brouwer’s local champions is a who’s-who of Cleveland’s classical ensembles and soloists. In addition to student groups and contemporary music specialists, she counts regular premieres and other performances by the Cleveland Women’s Orchestra, the Cavani Quartet, members of the Cleveland Orchestra, the Cleveland Composers Guild, and pianist Shuai Wang, to name a few.

Her full resume is even more distinguished. The list of orchestras, chamber ensembles, and festivals that have performed Brouwer’s music outside Cleveland would be the envy of almost any living composer, and the awards she’s received, if framed and hung, would fill a small room.

Brouwer’s music “has found an enduring place on the nation’s concert programs,” said Keith Fitch, Brouwer’s successor as head of composition at CIM, calling her “one of our most accomplished and well-regarded composers.”

Prominent among Brouwer’s recent local performances was a four-concert presentation of her 2009 Viola Concerto with Cleveland Orchestra violist Eliesha Nelson and CityMusic Cleveland, a professional chamber orchestra known for presenting free concerts all over Northeast Ohio.

Indeed, so notable was the occasion that it earned a review in the well-known journal “Seen and Heard International.” Brouwer’s concerto made “a powerful expressive point,” the critic wrote, citing a moment when percussion made “a glowing halo of sound” in contrast to the rich, vivid tone of Nelson’s viola.

“Brouwer’s reputation keeps expanding,” the critic concluded. “Her striking but accessible music is always worth hearing.”

“The piece was so well received,” Brouwer added. “I got so many wonderful comments.”

It’s been like this a long time for Brouwer. Like many composers, Brouwer needed time to get established. Once she found her footing, however, and her voice, a unique fusion of traditional and modern influences, she took off and never looked back.

Brouwer’s musical career began on the stage as a performer. After earning degrees from Oberlin College and Michigan State University, the Ann Arbor native entered the working world as a violinist in the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra. Later, she earned a seat in the Dallas Symphony Orchestra.

For that reason, to this day, she’s still enamored with the sound of an orchestra, enthralled by the limitless sonic palette it offers, even as she has written for dozens of other combinations as well. She also hasn’t lost her love for melody, for a theme that lingers in the ear.

But performing other people’s music, at the behest of a conductor, wasn’t Brouwer’s thing. Not really. What she wanted to do was to compose, to be the one supplying the music. Never mind that in those days women were still a rare presence in composition.

“I just had this creative urge all the time, and I felt I needed to write,” Brouwer recalled.

This led the violinist back to school, for a doctorate at Indiana University, and from there to her first teaching role, at Washington and Lee University. Then came Brouwer’s biggest break: a call from CIM, where she picked up the mantle of head of composition from the great Donald Erb, one of her many distinguished former teachers.

At CIM, Brouwer entered a kind of golden era, producing several of the pieces she still regards as favorites. Highlights from this period include “Rhapsody for Orchestra,” for the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, and “Aurolucent Circles,” a concerto for percussion, recorded by percussionist Evelyn Glennie, the Seattle Symphony, and conductor Gerard Schwarz.

All the while, Brouwer deepened her impact on the field through her teaching at CIM, helping a whole generation of younger composers find their voices in relation to hers, which by then had become distinctly recognizable.

“Her music – always well-crafted and engaging – effortlessly draws the listener into her world, one of beauty, color, and expression,” Fitch explained.

That momentum has continued in Brouwer’s post-CIM career.

Soon after stepping down from teaching, Brouwer founded Blue Streak Ensemble, a lively crew dedicated to contemporary music. This was no vanity project, however. Blue Streak engaged not only with Brouwer’s music but with composers of all stripes, helping to fill what was then a rather significant void in the field.

She also remained prolific as a composer, turning out a wide array of pieces for everything from solo piano to full orchestra. This was when her Viola Concerto came into existence, along with a Violin Concerto, a symphonic drama for CityMusic Cleveland, and a bevy of chamber music.

Cleveland remained her home all the while, for one simple reason: It’s the most musical city she knows.

“There’s a lot of wonderful music going on here,” Brouwer said. “The level of expertise and ability is just incredible. I’ve been to a lot of [concerts elsewhere] and in all honesty, Cleveland is just better.”

Eighty-five is a milestone, no matter one’s field. That, though, isn’t what Brouwer is celebrating. No, all she’s really thinking about are the commissions on her plate and the stack of older works awaiting revision or arrangement for other instruments.

A celebration of her birthday awaits in February at CIM, where she is now faculty emeritus. In the meantime, Brouwer continues to enjoy the best gift of all, a level of success many composers never see, in which her music has taken on a life of its own.

“At this point, I don’t even know most of the people who are playing my music,” Brouwer said. “They’re just playing it because they like it, and that makes me happy.”