This is a blog about arts management and policy. But as someone who has led many students through the basics of international trade, and as your resident Canadian, I’m going to use this space for a few words on the current state of relations across the 49th parallel.

As bad as things are in the current tariff dispute, I don’t think it’s the worst thing happening right now. Targeting vulnerable groups is cruel, and worse. Recent Cabinet appointments are as unqualified as one could possibly imagine (under an administration claiming a commitment to meritocracy, no less). Handing the keys to the US Treasury over to the unconfirmed, unelected, unstable Elon Musk is perhaps the most dangerous aspect of this administration. But, as I say, I know a bit about trade, so if this is of use to you, ArtsJournal followers, then read on. If you are really interested in this, please follow Paul Krugman on Substack, the GOAT on international trade.

First, some basics. Why do we trade internationally at all? The US is a big country, and for all the various things we consume there is probably some way to arrange their production in the US. So why not just shut down trade? There are two big reasons. First, we are all better off if we can specialize our efforts on production, and take advantage of the economies of scale that result from that. But you can’t have specialization if the scope of your market is really small. If you lived in a village of just one hundred people, and you had a pact not to trade goods or services with anyone outside the village, you wouldn’t have much specialization – you would all be spending most of your day in securing food and shelter (there certainly wouldn’t be job postings for arts administrators). International trade gives you the largest possible scope, one huge market, allowing different places to specialize in different things. Second, international trade allows any country to specialize in those things in which it has what economists call comparative advantage. That’s a term worth defining, because it becomes important later.

Jane plays pedal steel guitar, and is in very high demand in Nashville as a session player. Years ago, while learning her craft, she did house painting to make ends meet. She became very good at painting, excellent in fact. She owns a house in Nashville, and the whole interior could really do with painting. She knows that while there are some good contractors out there, none of them are actually as good a painter as she is, in terms of quality, attention to detail, and speed at getting the work done. Does she paint her house herself? Unlikely, because that would mean passing up guitar gigs, which pay very well. She is better off taking the gigs, and just hiring someone to do her painting. Comparative advantage means that someone can do a job with lower opportunity cost – less value in forgone opportunities – than others. Jane has a comparative advantage in making music, but not in house painting, even though she is very good at painting. Joe the painter, who really only knows how to do this one thing, has a comparative advantage at painting.

With unrestricted international trade, regions and countries will devote more resources to where they have a comparative advantage, those things they are particularly good at, and with lower opportunity costs, than in other things, even if they are pretty efficient at everything. In my state of Indiana, we could grow wheat, but for the most part we don’t because corn and soybeans pay better; even if Indiana is perfectly capable of growing wheat, it doesn’t make much sense. Let them grow wheat in North Dakota and Saskatchewan, places that are good for growing grain but not awfully practical for growing other things. We could try to grow all sorts of tropical fruit in the US, enough to feed us all, but it would be expensive, require a lot of greenhouses and such – why not grow things that are well suited to US regions, and let the more tropical countries supply us with bananas and mangoes?

Everything I’ve written so far is bog standard economics, neither right wing nor left wing. They are old ideas: the gains from international trade due to the greater ability to specialize is in Book 1 of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, and the theory of comparative advantage was developed by David Ricardo in the early 1800s.

In any economy, business investment goes to where investors think the returns will be greatest. People look for career paths that look to offer them the best opportunities. And all this is for the good – our human and capital resources naturally gravitate to where they have the most value.

That sometimes means the sorts of economic activities we do will shift. Why don’t we make ordinary low-value textiles in North Carolina anymore? Because US comparative advantage does not lie in low-wage low-technology manufacturing. Many places around the world can do that, but in the US it doesn’t work as a business. Not because foreign labour in so cheap, but because US labour is so expensive – there are simply better-paying things to do here than to make towels and pillow cases. We do have manufacturing in the US, but it tends to be where we have a comparative advantage: high-skilled, capital intensive things like jet engines, farm machinery, and so on.

So, in a nutshell, the above is the standard tale for why governments should aim for trade between nations that has as few barriers as possible. It is why Canada and the US signed a free trade agreement in the 1980s, added Mexico to a North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994, which was renegotiated and renamed USMCA in 2019, the US President at the time stating: “The USMCA is the largest, most significant, modern, and balanced trade agreement in history. All of our countries will benefit greatly.”

The same person, who does not seem to be a man of his word, now is about to impose (at the time I am writing this – I don’t know what happens tomorrow) 25% tariffs on imports from Mexico and Canada.

What do tariffs do?

A tariff is a tax on imports: the US is planning to levy taxes on goods imported from Canada and Mexico. All reliable evidence is that tariffs are shifted forward onto domestic consumers, i.e. Americans will now pay more for goods imported from Canada and Mexico. Well, that seems bad, especially from a president who campaigned on lowering consumer prices. The Tax Foundation reckons the tariffs on Canada and Mexico alone (not counting tariffs on China, or any other place that occurs to him) will cost American households about $670 per year in 2025. But it gets worse.

Not all things we buy will directly face tariffs. Think of ordinary services you buy around town, not physical products: these for the most part have no international trade – plumbers, electricians, and so on. So some prices rise, and others don’t. American investors look at this and say “where have prices gone up? Maybe we can make some money doing that now, even though it wasn’t really profitable before.” Superficially that sounds like tariffs are creating jobs in the US. But they are not: they are shifting jobs, out of sectors that aren’t affected by tariffs and into ones that had a price increase. But that is not good: in our unrestricted North American free trade world, Americans worked and invested where they had comparative advantage. Now they are being shifted away from that, towards sectors that have been affected by tariffs. So our economy is less productive. But it gets worse.

As we very quickly saw, countries that have just had their exports suddenly facing tariffs don’t take this lying down, even Canadians have their limit. So US exporters will now find that they are restricted in being able to sell goods abroad. Watch these industries start to make some noise pretty soon. But it gets worse.

As Krugman pointed out in one of his columns, the point of North American free trade wasn’t just to get rid of trade barriers, it was to allow firms to depend on a future without barriers, and make smart investments based on that. The North American auto industry is completely integrated in production (indeed, Canada and the US have had free trade in auto parts since the 1960s). So all of this is thrown into chaos, and all firms will be making investments very cautiously, wondering what comes next. Countries that have joined the European Union don’t just get unrestricted trade throughout the EU, they get a promise of a future of unrestricted trade, which allows for major investments and job creation to occur. In North America that has now been torn up.

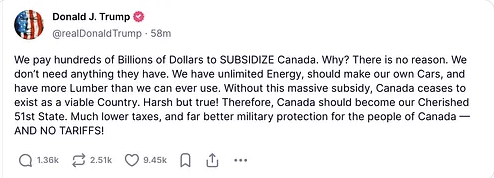

So, how does he justify doing this? I’m going to do something I typically avoid, which is to try to engage with what he actually says as if it is being said by a rational person. I’ll just take a short clip:

Although it is short, this will take some time to parse. To begin, we have to consider what is called the balance of trade. A country’s trade balance is its exports minus its imports. If that number is positive, it is a balance of trade surplus, if negative it is a deficit. Overall, the US runs an annual deficit of about $800 billion. How are we able to by more goods and services than we sell? How do we pay for them? The answer is that a trade deficit is financed by an inflow of foreign capital – foreigners invest in the US economy. Trump seems to hate the trade deficit, but likes foreign direct investment, and I doubt realizes that the two go hand in hand (this is not a specific economic theory; it is an accounting identity).

A thing we could calculate if we were interested, and Trump seems far more interested in this than it is worth, is bilateral trade balances: what if we just looked at the balance of imports and exports between two countries? The US has surpluses with some countries (the UK, Australia) and deficits with others (China, Mexico, Canada, Japan). I cannot stress enough: these do not matter. I have a trade deficit with my barber: I buy haircuts from her, but she buys nothing from me. I have a trade surplus with Indiana University: I sell them my labour, but buy little in return (now that my twins have graduated). My barber is not cheating me; I am not “subsidizing” her.

So, on to the post:

“We pay hundreds of billions of dollars to subsidize Canada” [I can’t bring myself to do the all-caps thing]. What he is referring to here is the bilateral trade deficit. Which is not a subsidy, which has nothing to do with subsidies. He does not understand what words mean. In any case, even if he does not know what a subsidy is, it is clear that the bilateral trade balance irks him. In detail, the balance is mostly driven by Canadian energy exports to the US Midwest; exclude that, and it is the US that runs a surplus with Canada, not the other way around.

“Why? There is no reason. We don’t need anything they have.” Well, the US doesn’t need Canadian products, but it does buy them, and if they went off the market the drivers of the Midwest would soon notice at the gas pump, and builders would notice at the lumber store, and don’t even get me started on Canadian lentil production. Americans don’t need Mexican agricultural produce either. But it sure is nice to have.

“We have unlimited Energy, should make our own cars, and have more Lumber than we can ever use.” To take this apart: no, US (or world) energy is not unlimited. The US is a big energy producer to be sure, but why rearrange distribution in the Midwest away from Alberta oil to Louisiana, which can sell it elsewhere? “Should make our own cars”: well, the US could do this. But why? Why shift jobs out of other sectors where markets say there is high value in production to put more people into the auto business? “Have more lumber than we can ever use”… really? I think there is a reason we see so much DIY furniture from Quebec in our local builders’ shops. He doesn’t face the obvious retort: if all he says his true, why are there imports from Canada? Why doesn’t my local Lowe’s stock wood entirely from Indiana instead of importing it from the North? Why do US refineries in the upper Midwest get their oil from Alberta and Saskatchewan? Because it makes economic sense to do so.

“Without this massive subsidy, Canada ceases to exist as a viable country.” Well, again with the “subsidy”: it’s not a subsidy. And without US trade Canada would certainly be poorer, but, as the saying goes, America is not the only fish in the sea, and Asia and Europe would be happy to accept Canadian exports of energy, commodities, and other goods.

“Harsh but true!” It’s not true.

“Therefore, Canada should become our Cherished 51st State. Much lower taxes, and far better military protection for the people of Canada – and no tariffs!” How romantic! Well…

Canada will not become the 51st state, and only someone with a complete ignorance of the country could ever imagine that this could be in the cards. It is, to be honest, quite insulting that he is willing to do so much harm to a country (and Mexico too) about which he understands nothing, and has no interest in understanding. But let’s fellow his, er, argument…

Lower taxes? Probably, though with the lower (and looks like absolutely gutted) public services of the US. And remember Canada will never, ever give up universal Medicare. Better military protection? It hasn’t really been an issue … living on the frozen prairie I did not fear that one day there would be Russian tanks coming down the highway from Moose Jaw.

No tariffs? Well, here’s the weird part (yes, it’s all weird). Canada has a bilateral trade surplus with the US. That is not anything that matters to anybody but Trump, but it seems to matter to him an awful lot. So, suppose by some magic Canada did become the Cherished 51st State (“The Cherished State” would be on license plates). It would still have a balance of trade surplus with the other 50 states! That wouldn’t change. Because states also have trade balances. Right now Texas has the largest trade surplus vis a vis the other 49 states, driven mostly by energy exports. Canada as a state would be something like another Texas. Making Canada a state would do nothing about the trade flows that he is so, inexplicably, concerned with.

It’s madness. I have written this with as much calmness as I can muster, but it is a response to a very stupid man, who does not understand even high school economics, and who has packed his palace with courtiers who to a person will tell him he is the smartest person in the world.

Good luck everybody.