In the sweltering days of early July 1913, more than 50,000 men gathered for a most unusual reunion. To mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, both Union and Confederate veterans from forty-six states traveled to the battlefield. The War Department provided field kitchens, latrines, cots, and long rows of tents. Boy Scouts and other volunteers pitched in to help the elderly pilgrims, a few of whom had to be taken away in horse-drawn ambulances when felled by heatstroke. Hundreds of photographs show the old soldiers, in Panama hats, white shirts, ties, and suspenders, with medals pinned to their dark vests. Their faces bristle with beards, mustaches, and side-whiskers, all gray or white, and they have that slightly shocked, frozen look that people often show in group photos from long ago.

A climax of the reunion came on July 3, when men who had taken part (or said they had taken part) in Pickett’s Charge and its repulse by Union troops met at the stone wall that had been a center of the fighting and shook hands across it. Photographers eagerly caught more images of the two armies’ veterans—some wearing parts of their old uniforms—greeting one another or dining together at long wooden tables. President Woodrow Wilson, the first southerner to occupy the White House in nearly half a century, arrived on July 4 to speak to “these gallant men in blue and gray”:

We have found one another again as brothers and comrades in arms, enemies no longer, generous friends rather, our battles long past, the quarrel forgotten…. How complete the union has become and how dear to all of us, how unquestioned, how benign and majestic.

Manisha Sinha does not mention the Gettysburg reunion in her provocative The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic, but it is an apt symbol of a central argument she makes: despite its surrender in 1865, the South eventually achieved at least a draw over the central issue that the Civil War was fought to resolve—the rights of Black Americans. In Wilson’s saccharine “the quarrel forgotten,” there was no hint of Abraham Lincoln’s famous words at that same battlefield fifty years earlier about “the unfinished work” of achieving “a new birth of freedom.” And much of what had happened in between was anything but “benign and majestic.”

Just as we talk about the First Republic, the Second Empire, or the Fifth Republic in France, so Sinha divides American history into phases, although the transition from one to another is not so neatly demarcated, sometimes taking years. Her focus is on what she calls our Second Republic: the promise of Reconstruction following the Civil War. This period, she points out, brought not just new rights for the formerly enslaved but hope for women and Native Americans, surprising flashes of solidarity with freedom struggles elsewhere, and “the forgotten origin point of social democracy in the United States.” All of this, however, was destined to be soon replaced by what she calls the American Empire—a regime that resumed seizing land from Native Americans, ruthlessly suppressed organized labor, and acquired its first overseas colonies.

Reconstruction was bitterly opposed by reactionaries, most notably the ghastly president Andrew Johnson (“This is a country for white men,” he wrote, “and…as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men”), who was in office from Lincoln’s death in 1865 until 1869. Sinha reminds us why the radical hopes of Reconstruction enraged racists like Johnson. There were corrupt or incompetent officials, to be sure, but besides safeguarding freedom for some four million slaves, Reconstruction was “a brief, shining historical moment” that held open a door to a different America. Both Black and white northern volunteers went south to work as teachers for former slaves who had previously been barred from all education. Even though most Black Americans never got their promised forty acres and a mule, some 25 percent owned at least a small amount of land by the century’s end. The Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution guaranteed them full citizenship and, for men, the right to vote. Johnson, nostalgic for his days as a slave owner (when he had really been, he claimed, “their slave instead of their being mine”), angrily vetoed one civil rights measure after another, but Congress usually overrode him.

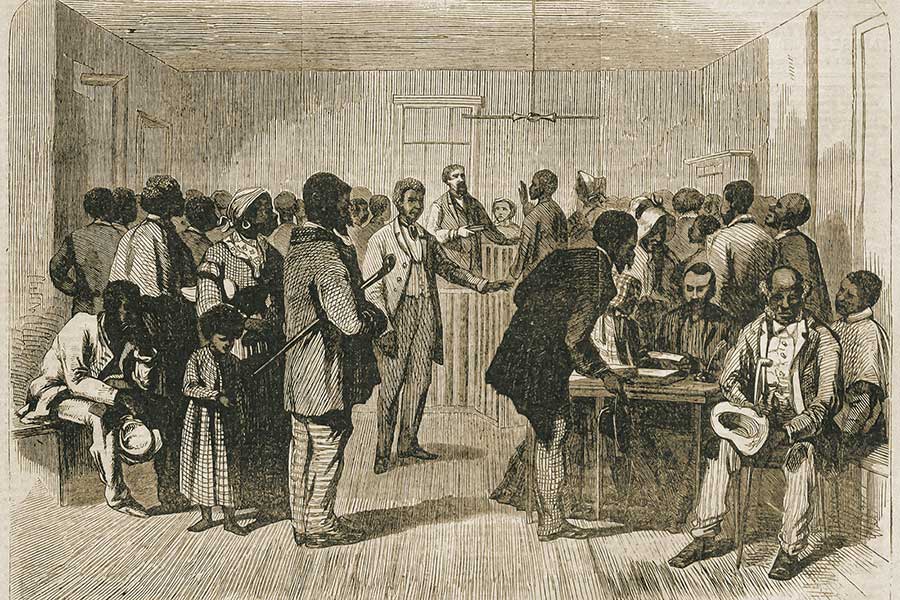

The most important Reconstruction agency was established in 1865: the Freedmen’s Bureau, “a sort of proxy state for African Americans” that did everything from helping them settle on public land to protecting them from wage theft and assault by white planters furious at losing their human property. Its schools taught more than 200,000 children over the course of seven years. It ran orphan asylums and more than sixty hospitals, and its medical workers also treated the newly freed in their homes.

All of this was still grossly inadequate to the needs of millions of impoverished men and women newly freed from slavery and surrounded by resentful, armed whites, but nonetheless, Sinha declares, “the Freedmen’s Bureau was the first government social welfare agency in US history.” Among other achievements, it founded and helped fund a number of what today we call HBCUs—historically Black colleges and universities. The most prominent, Howard University, bears the name of General Oliver Otis Howard of Maine, an ardent evangelical who lost an arm in the Civil War and was the Freedmen’s Bureau’s first commissioner.

Much of this picture is largely familiar from the work of historians ranging from W.E.B. Du Bois to Eric Foner. What Sinha adds to it are the intriguing signs of a wider radicalism that flourished, if briefly, as this idealistic moment began. Other historians have noted such connections, but I’ve not seen such an array of them compiled before. A Black division of the Union Army, Sinha writes, “called itself ‘Louverture,’ after the leader of the Haitian Revolution.” The country’s first Black daily newspaper, the New Orleans Tribune, declared that “whether the victim is called serf in Russia, peasant in Austria, Jew in Prussia, proletarian in France, pariah in India, Negro in the United States, at heart it is the same denial of justice.” One meeting of Black citizens of Illinois in 1866 warned “lovers of…constitutional liberty” of the dangers of a “coup d’état” such as the one staged in France some years earlier by Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, who declared himself Emperor Napoleon III. Their statement also spoke of “the aboriginal man of America, once the undisputed possessor of this continent,” who was “by coercion” robbed of land.

Indeed, for a time it seemed as if the Second American Republic might promise a better deal for Native Americans. Ely Parker, a Seneca, had served as a Union officer and aide to General Ulysses S. Grant; the surrender terms that Robert E. Lee signed at Appomattox were drafted in Parker’s handwriting. Four years later, when Grant became president, he appointed Parker commissioner of Indian affairs. Parker pushed for a more peaceful policy toward his fellow Native Americans: protection of their land rights, opportunities for education, and more.

The new constitutions that southern states adopted right after the war (almost all soon amended or ignored) were often wide-ranging. Alabama established an agricultural college and property rights for married women, and its constitutional convention resolved that ex-slaves could collect pay from their former owners for the period they were kept enslaved after the Emancipation Proclamation—surely America’s first reparations bill. Sinha, who has a frustrating tendency to race through long lists of events, quotes, laws, and resolutions, does not say if anyone was actually able to collect.

Although several of the conventions debated land reform, none of them enacted it. On the other hand, state constitutions

created tax-funded public school systems on a wide scale for the first time in the South, with South Carolina…and Texas making attendance mandatory…. They did away with undemocratic laws that penalized the poor, imprisonment for debt, as well as capital and “cruel and unusual” punishment for minor crimes. Most also protected laborers and sharecroppers by giving them the first share, or lien, on the crops they produced.

Finally, during Reconstruction, Black southerners were elected to office for the first time: to the US Senate and House of Representatives and—more than six hundred of them—to state legislatures.

All these advances, of course, were doomed. As southern whites reasserted their power, they swept away the Black officeholders; in 1874 eighty former Confederate officers were elected to Congress, and by 1910 one, Edward Douglass White of Louisiana, was chief justice of the Supreme Court. The early moment of promise had existed only while the defeated South was under military occupation. The last remnants of that came to an end in the Compromise of 1877, following a disputed presidential election. In return for Rutherford B. Hayes entering the White House, all remaining federal troops were withdrawn from the South. That left white southerners free to impose Jim Crow laws and to use poll taxes, lynching, and a ruthless campaign of murder, mutilation, and castration to terrorize Blacks, prevent them from voting, and ensure that the South would remain white-dominated and highly segregated for nearly a century to come.

It was also a South dominated by the wealthy, for poll taxes reduced voting by poor whites as well as Blacks. Again, Sinha’s wide perspective covers more than race:

Once in power, conservatives passed laws that adversely affected all poor and working people, including fence laws that cordoned off common grazing lands…. They also rescinded lien laws that protected sharecroppers and wage workers. Virginia…even authorized whipping for petty theft.

Central to the book is her assertion that crushing the Second Republic was a precondition for the rise of the American Empire. The white elites who overthrew Reconstruction, she writes,

helped make possible other antidemocratic policies and forces, from the conquest of the Plains Indians to the establishment of American empire to the crushing of the first mass labor and farmer movements.

The troops withdrawn from the South were then deployed against Native Americans. Gone from power was Ely Parker and his talk of peace. General Howard of the Freedmen’s Bureau later showed a very different spirit as he led a war against the Nez Perce people. “The rise of the Jim Crow South and the conquest of the West, often told as separate stories, were parallel events connected at a fundamental level,” Sinha writes. General William Tecumseh Sherman, leader of the Union Army’s march through Georgia, was in the field again, declaring, “We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux even to the extermination of men, women, and children.” Just as the progressives looked overseas, Sinha points out, so did the new empire builders: Sherman sent officers to England to learn how the British were so successful in their colonial wars.

Among those protesting the brutal seizure of Indian lands were many abolitionists. Lydia Maria Child urged in 1868 that “the white and Indian must jointly occupy the country.”* William Lloyd Garrison wrote that “the same contempt is generally felt at the west for the Indians as was felt at the south for the negroes.” He compared a ruthless massacre in Montana to British vengeance following the Indian Mutiny of 1857. Other abolitionists also thought internationally. When the Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner argued for civil rights, he compared the treatment of Blacks in the South to the sufferings of the lower castes in India, colonial subjects in Africa, and Chinese immigrants here at home.

The last Indian resistance was crushed in the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890. The big expansion of our overseas empire came eight years later as the United States seized Spain’s colonies, most importantly the Philippines, after the Spanish-American War. Many Confederate veterans had been welcomed back into the US Army for these campaigns. One of them, Major General Joseph Wheeler, got his enemies mixed up and shouted, as his men advanced against Spanish troops in Cuba, “We got the Yankees on the run!”

On the run, also, were labor unionists. Sinha writes that “federal troops, once deployed to secure freedpeople’s rights,” were now “being used on a wide scale to put down striking workers.” In an apt analogy, she reminds us that just as slaveholders had once talked of states’ rights but demanded a federal fugitive slave law, now postwar railroads and industries fended off laws about safety and working hours but demanded that government soldiers suppress unions. And they did, on a huge scale, from the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 onward. Intriguingly, Sinha mentions that the Pennsylvania Railroad magnate Tom Scott may have been one of the architects of the Compromise of 1877, although the full story of that fateful bargain will never be known.

It is poignant to imagine the America that could have been if the Second Republic had survived. If Lincoln had lived, or if he had chosen a more enlightened vice-president; if more federal troops had remained in the South; if their presence hadn’t been bargained away…there are many more ifs.

Some of those ifs could have given us a country with less bloodshed and more justice, but I doubt that they would have changed as much as Sinha implies. She writes, for example, that “the conquest of the West after the war…was not inevitable.” I fear it was. As the nineteenth century went on, the powerful new tools of the imperial age—trains and steamboats, the repeating rifle and the machine gun, telegraph lines to send orders to distant troops and officials—enabled colonizers or settlers to seize land across the world at an accelerating pace. It happened on the Great Plains under a capitalist democracy in the United States; it happened in Central Asia and the Caucasus under the absolute monarchy of tsarist Russia; it happened in Africa, India, Australia, and Southeast Asia under a variety of European regimes like Britain, France, and Germany. Even the great Frederick Douglass reflected a touch of this spirit when he said that there might be “a deficiency inherent to the Latin races” and advocated American annexation of what today is the Dominican Republic.

If the Second Republic had lasted longer, would Black Americans be better off today? Surely yes. But even under the best of circumstances, with both an administration and a Congress generous and enlightened, would the victorious North have had the necessary decades-long commitment required to undo the vast gulf in income, wealth, land ownership, education, and more that was slavery’s legacy? I doubt it. Short of revolution—which seldom has ended well—such differences are stubbornly enduring. In every country once blighted by slavery, the huge economic gap between descendants of slaves and masters yawns wide, even on the many Caribbean islands where the former far outnumber the latter and control the government as well.

I wish I could say that Sinha’s writing is as fresh as her perspective. It’s not. Important terms she uses, like the “contraband camps” where refugees fleeing slavery gathered during the Civil War, go undefined and barely described. She piles up cavalcades of detail about matters that are well known, such as the horrific years of terror that restored white supremacy in the South, while she rushes past other eye-catching but less familiar events. She devotes only part of one sentence, for instance, to the proposal by Senator Henry W. Blair of New Hampshire for a federally funded “uniform national system of primary and secondary education.” Versions of this bill passed the Senate three times in the twilight of the Second Republic, but never the House. Think how different America would be if a Black child in the Mississippi Delta had as much money spent on her education as a white one in Silicon Valley.

Sinha also never slows down to paint a narrative picture—whether of a particular community, say, that experienced the dreams and then the crushed hopes of Reconstruction, or of a typical meeting of one of the Black “conventions” of this period that she calls a “missing link” to the twentieth-century civil rights movement. She never gives us full, flesh-and-blood portraits of any of the major figures, especially those like Douglass who had a clear vision of the America that might have been.

Nonetheless, it’s valuable to have her history of unfulfilled hopes. The nation we had become when the frail Union and Confederate veterans clasped hands at Gettysburg in 1913 fell short of the one that at least some of those Union soldiers thought they were fighting for. As the white-haired men met, few Blacks in the South could vote, and in that year alone fifty-one of them were lynched. Native American children were forced to go to the notorious government boarding schools where they were punished if they spoke their native languages. By 1913 the American Empire was well underway; US troops were stationed in Hawaii, Cuba, Guam, Nicaragua, and the Philippines, a list that would grow far longer as the decades passed. One crucial promise of the Second Republic—the right to vote—was finally fulfilled in the 1960s with much effort, suffering, and sacrifice of lives. More remain to be realized. Given the new occupant of the White House, we may well find ourselves living under a Third Republic, with which those side-whiskered Confederate veterans might have been very satisfied.