The author has shared a YouTube video.You will need to accept and consent to the use of cookies and similar technologies by our third-party partners (including: YouTube, Instagram or Twitter), in order to view embedded content in this article and others you may visit in future.

While Chinaâs luxury market is slowing, population trends in Southeast Asia (SEA) are a significant opportunity to the fashion industry at large. By 2030, when 70 percent of ASEANâs population â which currently stands at over 670 million â is expected to have attained middle-class income levels, the consumer market could reach $4 trillion, according to McKinsey & Company.

Whatâs more, according to a joint report by Temasek and Google, among others, the digital economy in the six largest economies of the region â Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines â was worth an estimated $218 billion in gross merchandise value in 2023 and is on track to reach $600 billion by 2030.

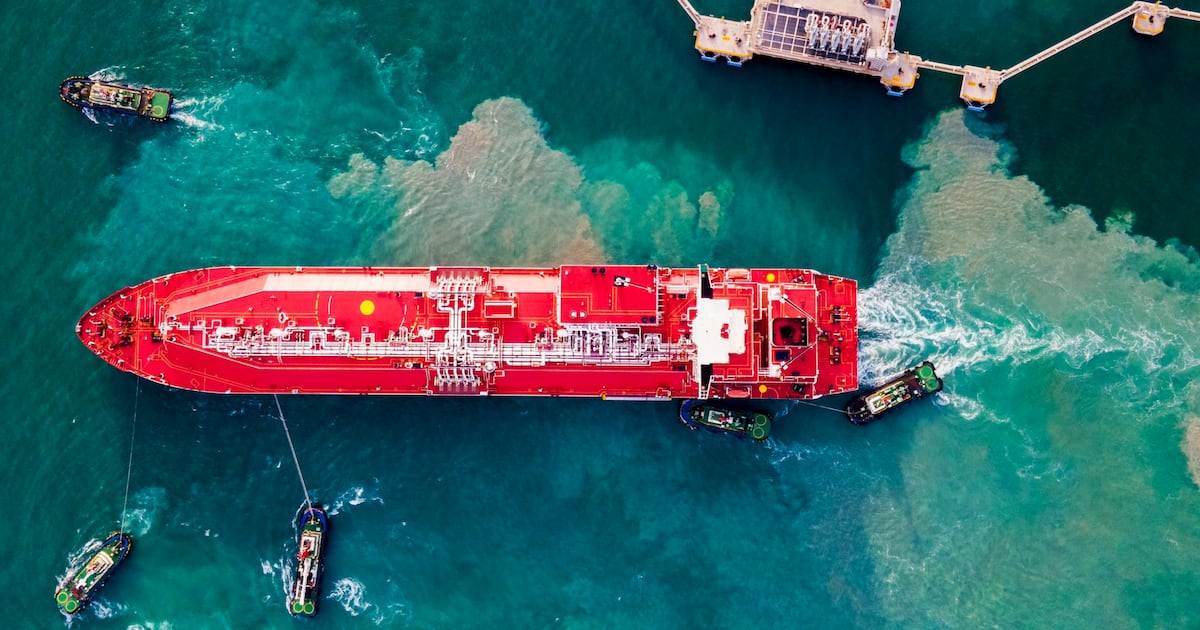

In addition to its proximity to these newly significant markets, Singapore is uniquely positioned between the two superpowers of our age. Almost all of East Asiaâs energy imports flow through the Strait of Malacca, and much of its manufacturing trade flows the other way. China is not only Singaporeâs largest source of imports, as it is for most countries in the world, but its largest source of exports too.

At the same time, America remains by far the largest single investor in Singapore, with S$574 billion ($428 billion) invested in the country at the end of 2022, compared with 156bn from mainland China, according to The Economist.

So what structure of regional supply will enable apparel and contemporary businesses to capitalise on the SEA growth trends and respond to the shape of that demand? And what positions a supply network as best in class in todayâs market?

In a recent BoF Live event, Sian Nee Ho, regional director of the Americas for the Singapore Economic Development Board (EDB) and Tony Pelli, practice director of supply chain security and resilience at BSI Consulting, discussed this opportunity and discovered best practices in minimising supply chain risk and optimising distribution to meet Asian and Southeast Asian demand.

Below, BoF shares condensed insights from the conversation.

Aligning Supply Chains to Growth Markets

SNH: There is really no one-size-fits-all approach. Companies will ultimately have to review their overall customer supplier base in Asia to identify their optimal supply chain strategy that allows them to best manage their costs, while also ensuring speed to market and overall resiliency amidst their supply chain disruptions.

What we are seeing is that consumers are increasing their expectations around accelerated delivery. Now, more brands are moving away from centralised distribution centres and adopting smaller, but more regionalised distribution centres to improve time to market. This could also be done through partnerships with various logistics players. Indeed, brands are increasing investments in supply chain management capabilities, including stronger data analytics to help with inventory optimisation across various distribution channels and countries.

In Singapore â because of our given proximity to major manufacturers, raw material suppliers and the growing Asian market â what weâre starting to see is that more brands anchor sourcing and distribution hubs here, and thatâs happened over the course of a couple years.

More brands are moving away from centralised distribution centres and adopting smaller, but more regionalised distribution centres to improve time to market.

The supply chain function as a whole is becoming a lot more strategic, and companies are actively thinking about how to expand those teams. I think most companies today have it as a global function. Those that are a bit more forward-thinking look to these regional supply chains as well â not just in the US, or wherever they are headquartered, but to have that across major regions where they operate as well, so that they can deal with unexpected circumstances or situations that come up.

TP: What weâre seeing is a more forward deployment of distribution centres that are closer to consumers, allowing companies to have more of those routes to market, through traditional stores, direct-to-consumer â enabling more of that sort of omnichannel distribution.

That was a huge buzz word four to six years ago; but itâs actually here now. Weâre still seeing lots of sea freight, moving goods around, thatâs not changing anytime soon. But, I think the way that companies are thinking about their supply chains â how they can get more SKUs, how they can get different products faster to their consumers, in that forward-deployed way I was speaking about â it ultimately requires changes throughout the supply chain, impacting your sourcing and buying and purchasing strategies, in addition to distribution.

Weâre also seeing faster changes in consumer demand â something that was popular a month ago is no longer popular. That really started to accelerate during the pandemic and hasnât slowed. That increased importance of speed to market can be a bit of a double-edged sword though â as it requires you keeping less inventory on hand, which means that you have less resilience throughout the supply chain. Itâs all about finding the right balance â which is what companies are grappling with now.

Best Practices and Global Standards

SNH: There are two aspects â diversification and disruption. Diversification â because I think weâre all familiar that geopolitical tensions are here to stay. When it comes to disruption, we do live in a troubled world today where there are two ongoing wars in both Europe and the Middle East â I donât think anyone could have imagined it five years ago. The Red Sea attacks have led to sea freight costs increasing three to five times since the start of 2024 and potential terrorism against China has led to inventory stock-ups as well, resulting in bottlenecks in port.

While China has served the interest of US companies for the last two decades, many companies now recognise the need to diversify their manufacturing and supply chain footprint to new growth frontiers. We have seen tremendous growth in Southeast Asia as an alternative from consumer products, semiconductors, industrial and even headquarter investments. So, the growth in Southeast Asia has also translated into an increase in inter-regional trade within Asia, with a larger proportion of Asian exports now destined for other Asian countries compared to the previous decades, where trade was more focused on exports to Western countries.

As a critical supply chain hub in Southeast Asia that facilitates trade flows, Singapore seeks to be that pressure relief valve for companies by providing some flexibility, certainty and efficiency. We are heartened to see the expansion of global leaders such as FedEx in Singapore, because we see them as the bellwethers of supply chain shifts, and these recent expansions provide validation on the opportunities in Southeast Asia.

Sustainability, Disruption and Mitigating Risk

TP: If you look at companies like Apple â they have used their supply chain strategy as a competitive advantage, by being in places before their competitors are. We saw that during the pandemic, when there were lockdowns in Shanghai, for example, they were able to quickly pivot to new areas of operation, new areas of sourcing and manufacturing. In the luxury industry, more broadly or in higher-cost goods, youâre able to use that as a competitive advantage, rather than just as a risk mitigation measure.

Of course, itâs not just them, but other businesses that are needing to be closer to consumers in places like Southeast Asia. You may see a large hub in a place like Singapore, and then smaller satellite hubs in places like Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia, that are more on the distribution end â essentially creating that central hub and spoke strategy rather than trying to distribute all from China directly. Thatâs the sort of scale of the investment weâre seeing.

Thailandâs another one where people may be investing as well, but on the supplier side, and itâs really being led by Vietnam. Youâre seeing a lot of the supply chain management companies that were based in Taiwan, South Korea and China â theyâre expanding into Vietnam now, but of course, theyâre using that to either avoid or mitigate certain risks. Certainly, when youâre looking at Vietnam or places like Cambodia, we want to make sure that these companies are sensitive to other risks that may develop, making sure that theyâre doing proper on-the-ground risk assessment of those suppliers from the beginning.

Innovating Supply Chain Technology and Predictive Analytics

TP: Companies really appreciate putting the analytics software in place that is able to feed them valuable data, but the issue is that they are unsure about how to then react when that data is presented to them. We see a lot of the time that companies are building systems or ways of working with that data in silos â buying and procurement using it for one thing, supply chain management using it for another.

We advise that companies should assess themselves internally before looking at any kind of software. Really thinking about how they are going to manage all of this new data, how are they going to react and how they are going to feed the data into their decision-making processes.

In terms of mitigating risk, the mapping out of your supply chains is the most important first step to act on, before even putting software in place.

In terms of mitigating risk, the mapping out of your supply chains is the most important first step to act on, before even putting software in place. Understanding where the raw materials are coming from initially is something that can be very messy â thereâs lots of manual data to sort through, many moving parts in terms of figuring out the provenance of those products and then overlaying digital solutions on top that make sure you can get a more real-time viewpoint. That makes it critical to have that static view of your supply chain first. From there, you can move to push and get more real-time visibility, and add the tools as needed to have that sort of second and third tier visibility.

Emerging Markets and Manufacturing Hubs

SNH: China will continue to be an important market for many companies, so itâs about finding out the level of presence that companies require in China to be able to adequately serve the needs of that population, while also finding an alternative when companies could then diversify some of their manufacturing and supply chain operations to ensure that is neutral and well connected.

The alternatives I mentioned: weâre seeing Mexico and Canada for more nearshoring of manufacturing and tech investments; and then India, for sectors such as more generic drugs and consumer electronics; not forgetting Southeast Asia for more consumer products, semiconductors and headquarter investments.

What weâre seeing with Singapore is that itâs a place thatâs committed to growing its air and sea connectivity through the airport and port expansion. And this will enable Singapore to remain plugged into and serve as a critical node in global trade and supply chain networks.

TP: If you look at it from a country-by-country basis, Indonesia and Vietnam certainly have large populations, with Vietnam being fairly well connected with China on one end and Singapore on the other.

Iâm not going to pretend that the sorts of issues in apparel supply chains or fashion supply chains donât exist in those countries, but thatâs why we encourage people to look at that through the entire process â from sourcing all the way through to business-as-usual management of their suppliers.

Donât just treat it as something that you only need to deal with when something goes wrong. Make sure that youâre building that in from the beginning â I think thatâs where weâll see fashion, especially in a place like Vietnam, have the greatest impact. Thailand and Malaysia may be a little less relevant for fashion, but they can add higher value manufacturing that some of the other regions cannot â again, all centred around Singapore as a hub for distribution through Southeast Asia, through the rest of East Asia and then onto the rest of the world.

We may see East Africa emerge in the longer term as well as a hub for manufacturing. Again, a lot of the freight that comes out of there is going to pass through Singapore as well. Thatâs my overall take on whatâs developing in the region where youâre seeing the strengths and weaknesses of individual countries.

If companies are smart about it, they can manage those weaknesses, as well as actually turning them into a competitive advantage for being able to quickly shift and change their supply chains as needed.

This is a sponsored feature paid for by EBD Singapore as part of a BoF partnership.